Beyond Development - Building Sustainable E-Infrastructure Through Effective Handover

Authors

Emma-Lisa Hansson, Jarno Laitinen, Susanne Ketill Groth, Ahti Saar, Anders Sjöström

Target audience

The target audience for this article is:

-

Project managers in e-infrastructure and technology fields.

-

Funding bodies and organisations supporting research and development.

-

Individuals involved in governance and operational transfer of complex projects.

-

Anyone interested in the long-term sustainability of research infrastructures.

Introduction

In the complex world of e-infrastructure and technology projects, the journey from development to sustainable operation is often fraught with challenges. While the initial ‘building’ phase garners significant attention, the crucial handover process – the bridge between project and permanence, is frequently overlooked. The Puhuri 2 NeIC project recognised this gap and dedicated substantial effort to defining a robust handover process.

Given Puhuri’s value to a broad range of service providers, it is important that the process of transferral of the system, from development into governance and operations, is founded in a transparent and robust process and methodology which can ensure that the delivered product can be sustainably maintained over the foreseeable future. These processes are highly valuable for ensuring the delivery of developed systems and long-term sustainability, especially within cross-national collaborations such as NeIC.

This blog post aims to share practical and key insights and recommendations gleaned from that experience, as well as report on our findings from a dedicated survey (aimed towards NeIC projects), offering valuable guidance for project managers, funding bodies, and anyone invested in the long-term sustainability of research infrastructures.

Key Survey findings

Survey results highlight the importance of structured, proactive approaches to project handover in e-infrastructure projects (NeIC):

- A significant majority of respondents indicated that their projects benefited from prior work, a trend consistent with the cumulative nature of project development.

- A lack of formal handover processes remains a major challenge.

- Role definition and sustainability require early planning and clear communication.

- Project-based funding remains the suitable model among participants.

- The findings validate Puhuri’s effort on structured handover processes.

Puhuri’s three-stage transferral process

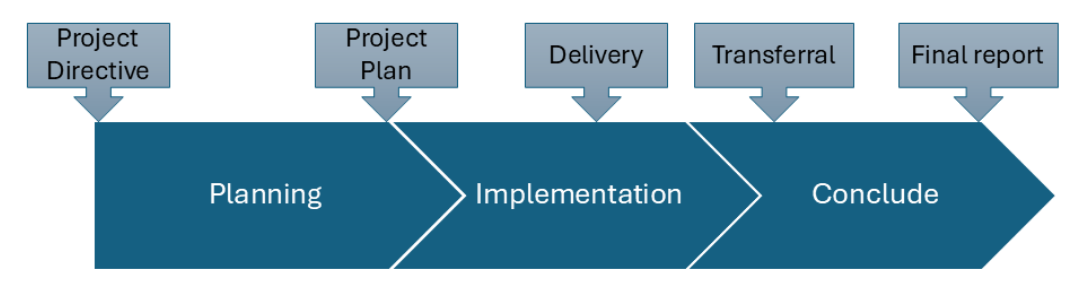

The Puhuri three-stage model is a further development of NeIC’s standard project model where the project ends with a transferral and closure.

Diagram 1: NeIC project model begins by defining the project outcome targets and then defining the content in a more detailed project plan, which is kept updated. The delivery and transfer process depends on the different projects.

The Puhuri2 project has developed key recommendations for the successful handover of its results to the receiving organization. These recommendations also apply to similar projects that are planning a service transfer and handover process.

The receiving organization should establish clear handover responsibilities covering governance, documentation migration, service operations, contract transfers or terminations, and necessary skill sets to ensure a smooth transition.

For similar projects, early planning is essential. Defining roles and responsibilities, implementing a structured transfer process, and maintaining effective communication and up-to-date documentation are crucial for a seamless transition and ongoing operational success.

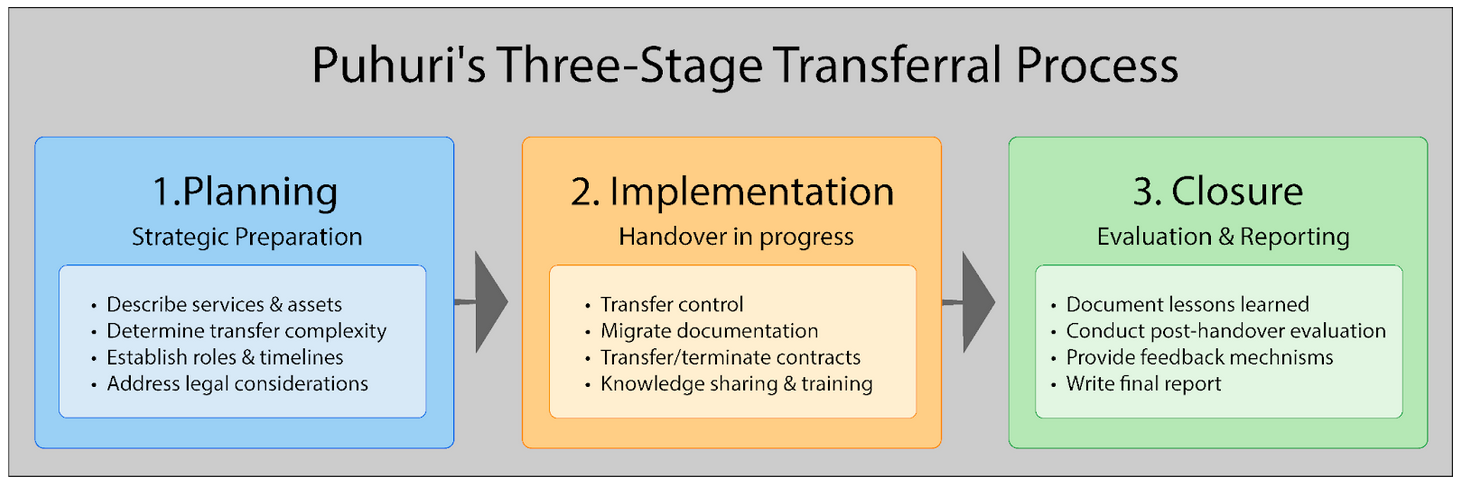

Puhuri’s Three-Stage Transferral Process:

-

Planning: The goal is to lay a solid foundation for a smooth transition.

- This initial stage focuses on strategic preparation. It involves defining the receiving organisation’s capabilities, selecting a suitable recipient, and conducting thorough negotiations.

- Key activities include:

- Describing Puhuri’s services and assets.

- Determining the complexity of the transfer.

- Establishing clear roles, responsibilities, and timelines.

- Addressing legal and ethical considerations (GDPR, IPR).

- Develop a structured timeline (e.g., a Gantt chart).

-

Implementation: This is the action-oriented stage where the actual handover occurs.

- Key activities include:

- Transferring steering and operational control.

- Migrating documentation and service operations.

- Transferring or terminating existing contracts.

- Ensuring skillset transfer through training and knowledge sharing.

- Using checklists to ensure all items are transferred.

- Effective communication and collaboration between Puhuri and the receiving organisation are crucial.

- Key activities include:

-

Closure: This final stage focuses on evaluating the transferral process and formally closing the project. The goal is to ensure a successful transition and identify areas for improvement. A NeIC Project is required to deliver a final report. Its content can be used as lessons learned. Naturally, it is not certain that new projects have been analysed and used all experience, but the NeIC’s project owners have experience.

- Key activities include:

- Documenting lessons learned.

- Conducting post-handover evaluations.

- Providing feedback mechanisms for both parties.

- Writing a final report.

- Key activities include:

Diagram 2: Puhuri’s Three-stage transferral process. The actions in the implementation phase shall occur in an appropriate phase within the project timeline.

Legal and Contractual Considerations

Conducting legal due diligence, securing necessary approvals, and updating contracts are crucial to ensure a smooth transition. This work should not be performed at the end of the project but be a vital part from the onset to ensure that problems do not arise.

The final transition of Puhuri can, from a judicial perspective, be seen as a transition on several levels. The transition of Puhuri from a framework of research-project/ temporary project phase to a permanent infrastructure solution, a transition from a cooperation project between members of NeIC to CSC as a legal entity and a transition from a non-legal entity to a legal entity.

These transitions represent several legal challenges. These issues typically involve contractual obligations, compliance, and financial liabilities. Below are listed some key legal concerns in such a transfer, even though not all of the issues have been relevant for Puhuri:

1. Contractual and Ownership Issues

- Project establishing: When establishing the project, make sure to consider the purpose carefully to avoid a contract format that is not suitable for the project’s purpose.

- Project Contracts: Contracts from the project phase do not automatically cover the conversion to the permanent phase, requiring renegotiation.

- Ownership Rights: Ensuring a clear legal transfer of assets, liabilities, and responsibilities from the project entity to the permanent infrastructure owner.

- Intellectual Property (IP) Rights: When the project involves IPR, legal ownership of materials must be clarified

- Governance: Determining who governs the project and the mandate of each project participant.

- Contracts with a third party: Transferal of an existing contract with a third party if a continuation of collaboration is wanted.

2. Regulatory and Compliance Issues

- Regulation and compliance issues: A transition of ownership can have a regulatory and compliance impact due to different national laws or the parties changing roles e.g. compliance with GDPR.

- The GDPR processor and controllership may change during the handover if the services process personal data. In that case, an update, for example, to the Data Processing Agreement, Privacy Notice and communication towards the Data Subject is needed.

3. Financial issues

- Funding Agreements: The transition may involve new financing structures, requiring legal clarity on debt, ownership, and repayment terms.

Project Handover Checklist

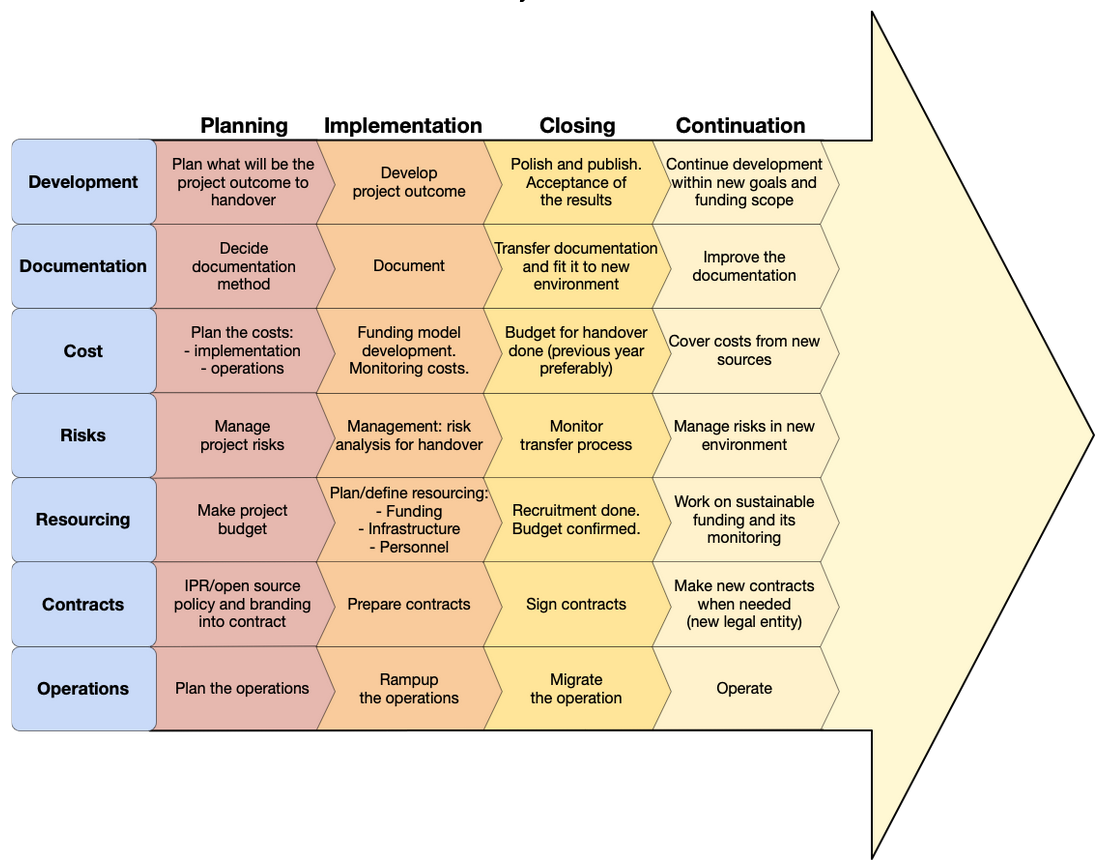

The diagram displayed in the image presents a structured approach to transitioning projects from development to ongoing operations. This framework addresses seven key dimensions across four project phases.

The framework recognises that projects do not simply end but evolve into operational entities or get handed to new teams. By mapping activities across Development, Documentation, Cost, Risks, Resourcing, Contracts, and Operations dimensions, it creates a comprehensive roadmap for successful transitions.

Each dimension progresses through Planning (establishing initial requirements), Implementation (creating deliverables), Closing (formalising handover), and Continuation (sustaining operations). Notable elements include planning for handover from the beginning, ensuring knowledge transfer through documentation, managing financial transitions between fiscal periods, addressing handover-specific risks, confirming resource allocations, handling contractual requirements, and maintaining operational continuity.

This systematic approach helps organisations preserve project value beyond traditional delivery milestones by explicitly planning for the transition from inception, reducing handover friction, and maintaining momentum as projects evolve into their next phase.

NeIC piloted an affiliate model where a small amount of funding could be applied to support the benefit realisation activities after the Project finishes.

Diagram 3: Project handover checklist.

In essence, Puhuri’s process emphasises meticulous preparation, active implementation, and thorough evaluation to ensure a seamless and sustainable transfer of its e-infrastructure services.

NeIC project practices and survey results

Six NeIC projects, both current and former, provided a valuable snapshot of common practices and challenges for this blog post. The survey revealed several key trends regarding project transferral and sustainability.

Key Findings:

- Project Continuation and Governance:

- A majority of projects experienced continuation of their outcomes, often through further funding or integration into other initiatives.

- However, a significant portion lacked a clear plan for future governance, highlighting a disconnect between project continuation and structured sustainability.

- Lack of Formal Handover Processes:

- A striking finding was the absence of formal handover checklists or plans in most projects.

- This suggests a widespread need for standardised procedures to facilitate smoother transitions.

- Identifying Handover Elements:

- While most projects didn’t struggle to identify handover elements, some faced challenges, particularly with intangible outcomes like knowledge and algorithms.

- Role and Responsibility Clarity:

- Identifying post-project leadership and responsibility proved challenging for some, indicating a need for clearer role definitions beyond the initial project phase.

- Recipient Capabilities:

- Defining recipient capabilities was generally not a major hurdle, but some projects noted broader difficulties in defining necessary skills.

- NeIC’s Role:

- NeIC’s contribution to future governance varied, with some projects reporting valuable support and others noting its absence.

- Handover Success and Challenges:

- While some projects reported successful handovers, challenges persisted, including maintaining project member engagement and transitioning to operational models.

- Documentation and Knowledge Transfer:

- Most projects documented knowledge and lessons learned, but the level of formality and accessibility varied.

- Most projects did benefit from previous projects.

- Deliverable Ownership:

- There were mixed results on the clarity of deliverable ownership after handover, highlighting a potential area for improved clarity in project agreements.

- Funding Model Suitability:

- Most projects felt the project-based funding scheme was more suitable than an operational infrastructure funding and service owner model.

- Resourcing of the continuation: As the funding may be reduced and the priorities may change, the involved people will also change.

Summarisation and recommendations

In Puhuri 2, governance and sustainability are one of the key focus areas. For any collaborative infrastructure project, sustainability is crucial for long-term success. Addressing governance early is essential. Even when the intended recipient of project outcomes is clear from the beginning, continuation becomes suboptimal without proper foundations for ownership transition.

Since NeIC projects aren’t legal entities, identified contractual issues must be resolved between organisations, and if necessary, a legal entity must be decided upon when the project is established. In the Puhuri 2 project, an agreement was made between the partners to agree on a legal entity in the form of a Guardian. The aspects of a Guardian were described in the collaboration agreement.

While NeIC funded development projects are Puhuri’s original target customers, operational services are funded by national providers rather than NeIC. These service owners are, therefore, key stakeholders, and Puhuri must continue supporting them. Given the Puhuri services added value to a wider range of service providers, transferring the service from development to governance and operations requires a transparent, robust process to ensure sustainable maintenance for the foreseeable future.

Puhuri project collaborated with NeIC Project Managers to develop policies, methodologies, and collaborations that can benefit future NeIC projects. By sharing our insights, we hope to empower other projects to build sustainable legacies and contribute to the advancement of collaborative e-infrastructure.

As Puhuri 2 concludes, we offer these questions for the broader e-infrastructure community:

-

How can we collectively build a more sustainable future for research e-infrastructures?

-

What challenges have you faced in ensuring the long-term sustainability of your projects?